"Perception's Delusion" Series 2022-present

"Things Thinking" at Rory Devine Fine Art 2023

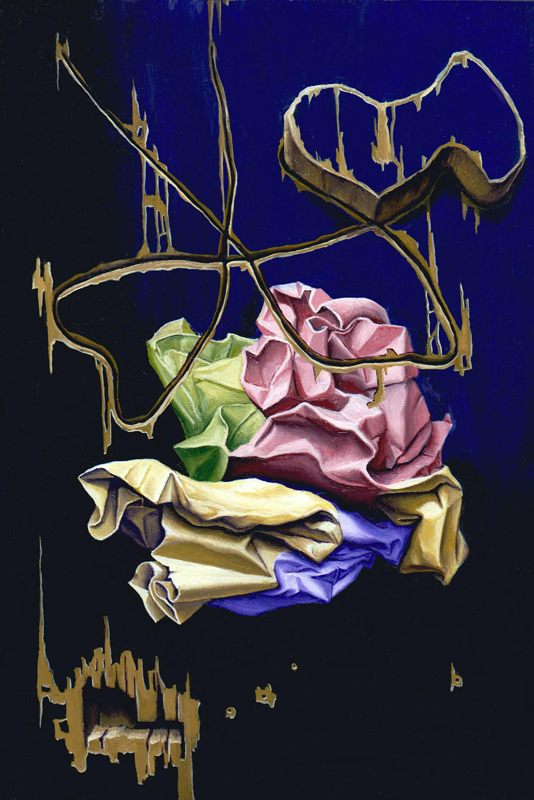

"All That Is Solid Melts Into Air" 2022

"Close Quarters" 2019-2021

"Divided Brain" Drawing Portfolio 2019

"Behavior" Art Book 2019

"Stacks And Folds" 2019

"Empty Space Is Not Nothing" 2014

"Physics 101" 2013

Paintings of Wood Constructions 2008-2012

Art In Public Series 2006

Sculpture 2000-2005